Crush: Paintings by Gail Baxter-Cohen

by Jill Conner

1988, Stardust, oil painting and pigment dissolved in varnish medium, 72×72 inches

Gail Baxter-Cohen is an artist who currently lives and works in New York City. Cohen hails from Chicago, Illinois and spent the late 1960s living in San Francisco, California at the peak of the bohemian era, when the Civil Rights Movement gripped every niche of the world. Artists questioned the basis of traditional genres in all media as political protests and performance art destabilized the significance of the white-cube interior found within mainstream art galleries and museums. Re-using and re-articulating found material was the primary way that artists effectively altered the face of traditional media.

Cohen began figurative drawing in her youth. While living along the gritty Mission Street in San Francisco, the artist began to sketch as a response to both personal and political upheaval. “It emerged as a need,” Cohen says. Upon relocating to New York City during the early 1970s, the artist enrolled at the Art Students League and studied paintings with American Abstract Expressionist legends Knox Martin and Richard Pousette-Dart. Since the early 20th-century, the Art Students League became synonymous with Robert Henri and his coterie of painters who utilized representation painting to capture scenes of everyday life that took place across the economic spectrum.

American Abstract Expressionism linked with the school’s history of figuration since the painting process was emblematic of freedom and prosperity that followed in the wake of World War II. Prewar, figurative artists such as Will Barnett worked fluidly alongside this new turn in America’s artistic identity. Martin and Dart in particular mentored students to eliminate any suggestion of visual illusion and figuration while maintaining a strict focus on both material and color, the Postwar Formalist paradigm of Clement Greenberg.

However by the 1960s this approach gradually transformed into a hermetic, theoretical approach that appeared untimely and out-of-step with an array of socio-political events that coursed throughout society, leading up to the Student Revolution of 1968. Since 1951 the atrocities wrought by the wars in Korea, the Falkland Island and Vietnam, gave shape to a larger awareness while Civil Rights activists such as Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Malcom X, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. and David Richmond highlighted the growing conflicts arising from racial segregation. Painting, and art in general, was no longer a medium for the select few but rather for anyone who needed to capture difference. Density in numbers spoke effectively to political power.

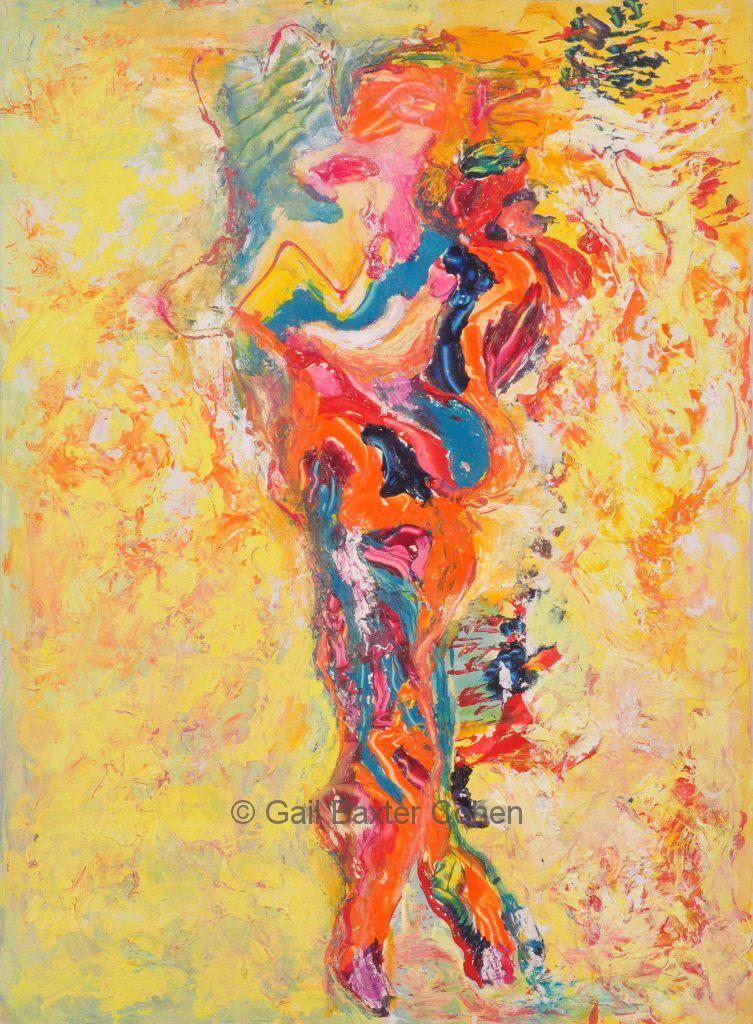

Dancing Lady, acrylic paint, charcoal, marker on paper 2010, 30 x 22 x 2 inches (76 x 56 x 5 cm)

For Gail Baxter-Cohen, abstract painting felt like a gesture that went nowhere beyond the canvas since it did not effectively respond to the world around. Cohen became a multi-media artist who utilizes elements of mundane living as part of her paintings process that continues to dissect traditional surfaces while building up texture. The artist also recycles objects into her work, breaking them down into elements that reshape narrative. “Art pretty much has a microphone in it,” Cohen states. “It tells one all about your life.” The artist’s work is primarily abstract but incorporates the figure sparingly to reveal the differences between genres, shaking our perceptions that are attached primarily to to pop iconography and metaphor. Like Robert Rauschenberg, Cohen utilizes the flat two-dimensional surface to engage physical space.

“Stardust” (1988) and “Red Man (1988-89) are two paintings that capture Gail Baxter-Cohen’s trademark gestural line, oscillating fluidly between figuration and abstraction, reconciling opposites while creating connections. The wisp-like appearance seen throughout the blue, white and black hues of “Stardust” initially gives the impression of a constellation shining across the midnight sky. However the sheer density of color creates an ocular experience that recalls both Richard Pousette-Dart’s painting titled “Night Landscape” (1969-71) and Claude Monet’s paintings of his gardens at Giverny.

Cohen’s predominantly yellow painting titled “Red Man” features a series of complimentary opposites that subsequently move well together. The bright, charged background frames a funnel of orange, blue, pink and red that mix together on the surface of the painting while showing the vague trace of a mask near the top center, while two feet seem to step apart near the end of the composition. In this piece Cohen reaches outside of the subdued color palette, characteristic of American abstract painting from the mid-twentieth century and, instead, constructs a vibrant viewing experience thereby moving the concept of abstraction away from the art object and toward the perception of the viewer.

The events of September 11, 2001 took an emotional and physical toll upon the artist which was first rendered in “Afterward” (2001), a pastel and charcoal drawing, portraying nothing but a cloudy haze that barely gives way to a faltering skyline. Cohen continued to channel the energy she had felt forty years earlier into a three-panel series titled “Three Hundred and Sixty Paintings” (2001-2007) wherein the artist crushed, dismantled and reformed all of her previous paintings into three tall panels that measure 6-feet tall and nearly 2-feet wide. Each one consists of painted scrim and canvas that carries a gray funerary overtone, punctuated with floral pastel colors. These pieces collectively suggest a period of mourning for the artist that culminated in a shrine to remember the lives lost throughout the world as a result of international terror.

By 2005 disjointed, sculptural surfaces become the primary focus of Cohen’s work. Painting seemed too passive, whereas applying found objects directly to the canvas or wooden stretcher made her work more viable. “Assemblage” (2005) is a 2-foot by 3-foot frame of wood panels that puzzle together but appear flush with the edges, portraying the complex nature of architectural and psychological façade, suggesting this stoic front as another vulnerable structure. Built-up layers of white encaustic and oil paint in “The Slash Building” (2004) reveal Gail Baxter-Cohen’s abstract painting at its best. Thick strokes of expressive texture can be seen overlaying one another, creating a sense of tactile dimension while faint hues of yellow and red combine evenly with the artist’s additional but subtle application of string and yarn.

The Slash Building, encasutic, string and oil paint, 2004, 56 x 52 x 3 inches

In 2011 Cohen took a more reductive turn, building up mixed-media abstractions, but maintaining a flat, two-dimensional surface that played only upon line and color. “Red Line Painting” from 2011 consists of berries, beads, string, glue, oil paint and encaustic upon canvas that first creates nothing further than a series of red horizontal lines that appear to run horizontally upon a built-up white background, similar to the surface seen in “The Slash Building”. However the depth of Cohen’s “Red Line Painting” only makes itself available upon closer view, where the mesh of materials can be seen, revealing a methodical meditative process. “Feather Line Painting” (2012) carries the same use of line as seen in the previous piece; however here, the artist introduces more colors such as blue, pink, orange, green and red. Different colors appear horizontally, covering a strand of either string or yarn that stretches across a white background. Feathers are mixed into the background, masquerading as marks left by painted brushstrokes, stressing textured character of abstraction. A piece that predates both of these pieces is “Abstraction #1” from 2009 showing two horizontal yellow lines that suggest a Turner-esque landscape over a thick layer of white with slight accents of orange, red and pink.

“Medicine Man” (2012) is the artist’s largest sculptural painting. Presented as a wooden box on a wall, this weighty piece bursts open at the top with voluminous fabric and feathers that lean outward into the room. Cohen’s additional application of pink and gray paint to these materials accentuates the physicality of her painting even further. This piece echoes the Combines of Robert Rauschenberg, except in this instance the artist does not provide any specific objects beyond the materials themselves.

Gail Baxter-Cohen’s paintings are about immediacy. Rather than reiterate art historical forms, Cohen confronts the picture plane as an empty space that is available for experimentation and negotiation, echoing the socio-political events that became an influence early on in her career. Feminist theory underscores all of her work, responding to her mother’s death from breast cancer as well as the custody battle that she had once fought for her daughter. After leaving the Art Students League, Cohen attended New York University where she encountered visiting artists such as Lousie Bourgeois and Judy Pfaff. Pulling from Knox Martin’s instruction “to see”, Cohen created a series of ephemeral art objects that were based upon her personal experience. Permanence and monumentality were not relevant to the fast pace of her lived experience. From surfaces of found wood to meshed canvas, Cohen suggests line as a tangible material that also appears as thread winding across an empty, stretched surface. Recently the artist extended her choice of paint medium to women’s cosmetics. By deconstructing surfaces with mixed and non-traditional media, Gail Baxter-Cohen reveals the ever-shifting nature of abstract painting.

Jill Conner is an art critic based in New York City